Path Dependency

My last article was over the main things I learned in my 21st year of life. Now at 22 I want to write about the single biggest investing concept that I have integrated into my own system.

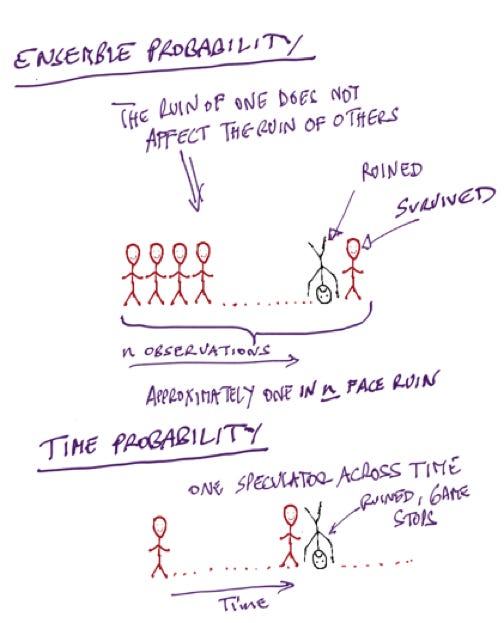

Path dependency is the realization that you are not THE average.

To Paraphrase from Nassim Taleb’s Antifragile picture a game of Russian Roulette. If there is one Bullet in a five bullet chamber your odds are ⅕. Of being shot. If you were paid some multiple of your net worth every time you took the shot you may be tempted to take 2, 3, even four shots. But if you get shot you’re dead. It doesn’t matter how much you won. You go to zero.

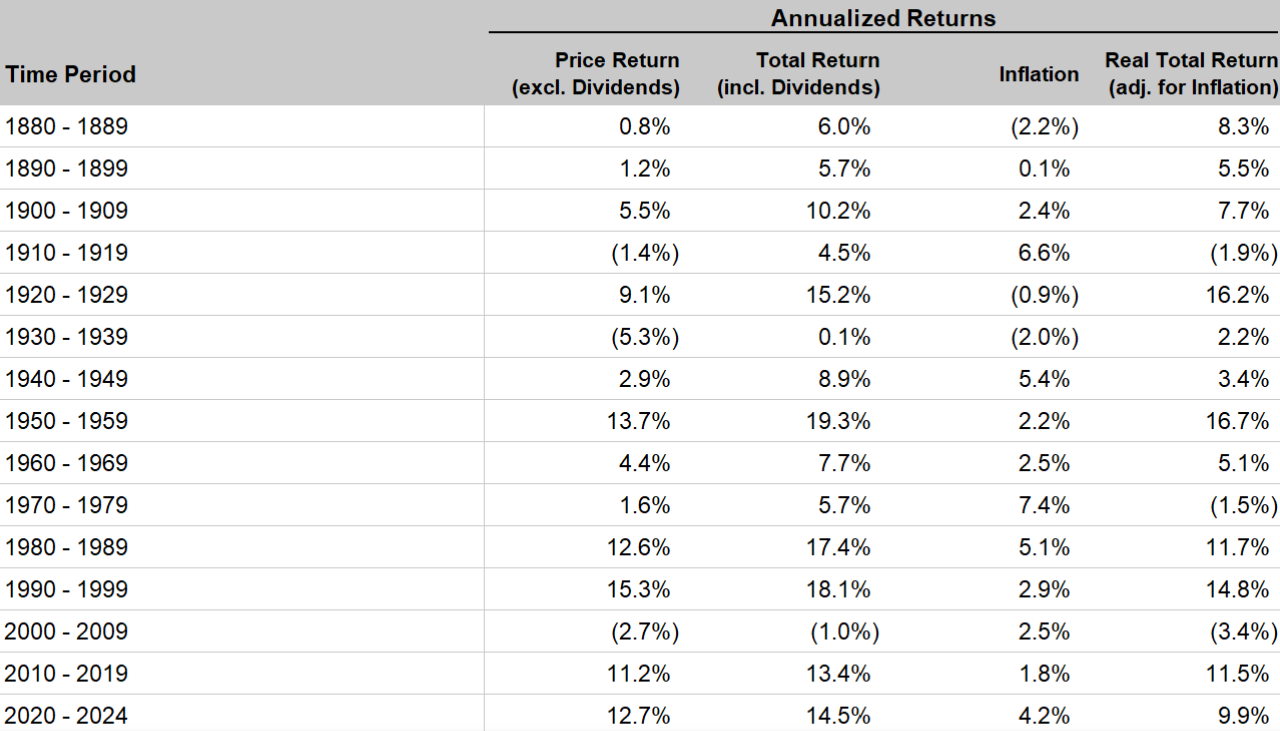

It is a common adage that the market tends to return about 10% on average(this figure is before taxes, fees and inflation but after dividends.)

But let’s look at what has gone into this. If you were a US investor from 1950 to 1990 things were pretty good, you would have annualized an approximately 12% return

But if you were an investor who started in 1900 to 1940 your annualized return would have been about 6.9%

Then bear in mind if you retire into a market downturn you decrease total accumulation power because your income needs come out of the portfolio.

Here is what you can’t get away from. The equity risk premium. This is the risk component in risk and return. Volatility comes with a level of return above the risk free rate. You can’t control the risk free rate or the equity risk premium. But you have to stay invested. Investing is the most surefire to become wealthy. You cannot control the markets, you can only do the things which are going to survive and thrive over the long term.

If I have not made things abundantly clear, you are trying to minimize what needs to go right. You try to avoid blowups, that is normal. But what are you assuming that needs to happen for your investments to work?

Security Selection

The goal is to create a portfolio of companies that have the characteristics to survive various forms of chaos.

Leverage is the ultimate creator of path dependency in a portfolio and at the company level. Leverage means a company has an obligation into the future that must be paid. Ideally the cost of doing this is cheaper than the average cost of equity and the opportunity cost of taking on the leverage is worth it. However, leverage is the single most non-ergodic thing. Leverage is a compounder of failing and success, but all it takes is a single failure for leverage to become a huge risk. So both at the portfolio level and the company level I try to avoid leverage.

Recurring revenue, low churn, and high gross margins. This is the other side of the leverage coin. Revenues are inherently less stable than debt. A company has to pay their debts, but they can’t force customers to buy their products. But I will point out John Malone of TCI, now Liberty Group. He could build the assets for cable, take out lots of debt for the buildout, and the revenue was exceptionally stable. So even if he financed the majority of the asset buildout with debt, once those assets were built the cash flows they produced would be stable enough that it minimized the cost of ruin. This is where revenue churn becomes important. There is a misperception that recurring revenue means revenue stability. Think of some gyms. The revenue from customers is subscription-style, they make money month after month, but consumers frequently cancel. High churn points to limited pricing power and therefore, more path dependence. Finally looking at gross margins can be deceiving, the number isn’t necessarily as important as the direction. If a company can hold gross margins stable or go higher over time starting from a lower number is better than a business with high but declining gross margins. One points to a company that is able to flex pricing power while the other points to competition deteriorating profits.

Cashflow Generation. I have disclosed that I get the majority of my ideas either by copying other great investors, looking through SEC filings for unique situations, or by screening based on fundamental metrics. In the later case almost all of these fundamental metrics are some variation on a business which has robust cashflows and trades at a low multiple to those cashflows. I look at various definitions of cashflow to try and capture accounting quirks, compare depreciation and amortization, one time charges, changes in working capital, uncovering various discrepancies is where a lot of the excess return is, but you want to start with a data-set that improves your probability of finding good businesses. And cash flow is how the sausage gets made. EBITDA or earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization is the broadest and most stable. It represents cashflow but does not factor in working capital changes and may or may not include one-time charges or profits which can distort profit. EBIT or earnings before interest and taxes factors depreciation and amortization as a cost which can help significantly differentiate peer cost structures. Free Cash Flow and operating cash flow are the broadest but also generally the most subject to fluctuation. The explicit purpose of cashflow is to differentiate what cash was generated and lost by the operations of the business. But I am broadly only interested in companies that generate significant cash that they can then reallocate.

Capital Allocation and good management: this is a two-parter because they are truly side-by-side. I’ve never seen a management team where I thought their leadership was good but their capital allocation was poor or vice versa. I want to find investments who think in terms of net present value, opportunity cost, and leave the menu open for investment. Generally, I have gravitated towards companies with high shareholder yields, or companies which buy back more stock than they issue, pay down high interest debt and or pay dividends. I am not a “dividend investor” but in certain cases, stable businesses with low payouts as a percentage of free cash flow and high dividend yields can be attractive as a type of “equity bond” and help pad your total overall returns. But good capital allocation also looks like the freedom to take on low cost debt for high return projects or reinvesting at high incremental returns on capital.

Attractive Valuations: What is an attractive valuation? That is somewhat subjective, you should be willing to pay up more for a stable, high return, high growth business than an unpredictable, low growth, low return business. But my rule of thumb is to try and look for unloved industries and or companies which are of comparable quality but lower multiples than their peers.

In terms of multiples I love the work of Columbia Professor Michael Mauboussin who says you have to earn the right to use a multiple. 6x cashflow can be cheap, expensive, or fairly priced, depending on the business you are valuing. Thus why the prior principles are important.

So the whole point is you don’t need a lot to go right, but it’s clear that is a relative statement. The fix for that is base rates. Essentially we have to look at what has happened before under similar circumstances.

Among companies of the size, margin profile, industry etc that you are analyzing, how likely is it that your assumptions come to pass? For example, if my base case assumption on a business with between 1-2 billion dollars is approximately a 0% 5 year growth CAGR I have an approximately 16% chance of being too aggressive. If I assumed 5% CAGR then my chance of being aggressive jumps to 46%. The same idea applies to margin forecasting and exit valuations.

From there the question is related to what are the characteristics of the businesses that DO fail. It is not a perfect science, but I engineer most of my picks to minimize the need for things to go right.

(This is The Base Rates Book, a compilation of observations about prior events in investing from 1950-2015, while somewhat stale today the information within is still incredibly useful for formulating base rate cases) https://sorfis.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/The-Base-Rate-Book-Integrating-the-Past-to-Better-Anticipate-the-Future-September-2016.pdf

My biggest drawdowns have been due to path-dependent investments. I feel it is important I share my failures alongside my successes.

I still hold a stake in Owens and Minor, perhaps foolishly, perhaps not, but I took a big drawdown on it because my thesis showed that they were dependent not only on good operating performance of their patient direct business, but also fetching a good price on the sale of their legacy business. The reason I have not immediately exited after the sale is that the patient direct business appears solid if underwhelming. However, the sale price for the legacy medical business was disappointing. A similar thing happened with JELD-WEN the maker of doors and door frames is executing on a turnaround plan, and while trading below book, the plan is primarily on an operational turnaround which is yet to fully materialize, especially in a sluggish housing market.

Portfolio Construction:

I have spoken about what I have found to be the less discussed part of a “survival portfolio” one built to weather all types of economic conditions. But portfolio construction has to have its time, and not just theoretically talking about abstract ideas, but ways to optimize the portfolio in practice. This is being published before Christmas so there are a few days left but the portfolio experienced ups and downs but approximately matched the S&P500 return. This is primarily due to the aforementioned JELD-WEN and OMI which had significant losses from path-dependent factors.

The single most debated portfolio management topic in value investing is concentration. From fund managers like Monish Pobrai or Norbert Lou at Punchcard with around 6~ stocks to Tweedy Browne, Thomas Russo, Giverny Capital, Walter Schloss and others which have 50-100+ names. Even in diversified portfolios, a company like Vulcan value has ~65% in the top ten names but 40 stocks in the portfolio. Or Berkshire Hathaway with roughly 80% in the top 10 and the other 20% across 30 other stocks. But there is also Henry Ellenbogen of Durable Capital Partners with only ~44% in his top ten across 48 names.

My take on Concentration is this. Evidence from Alpha Theory, a research service dedicated to optimizing portfolio management techniques for value investors, says that there is a correlation between the largest sized-positions and their outperformance. In other words the top 10 sized stocks ten to outperform the bottom 10 etc. But when comparing the probability of outperformance of a particular position vs the market the sweet spot tends to be 10-30 names. I have seen that number go as high as 50 depending on how diversification benefits are measured. I think the traditional concentration and sizing argument is missing the influence of control and liquidity. Again framing it in terms of path-dependency “what has to go right” you should size things more conservatively if they are illiquid or if you have a lack of control. This is why I think it is fine when Trian Funds has a third of their assets is Janus Henderson, they own 20% of the company. Or Fairholm having nearly 80% of assets in St. Joe but the CIO is also the chairman of the company’s board and the fund owns 1/3rd of the company. This is like Buffett controlling enough of Sanborn Map that he could push for what he wanted to happen. So he could put 50% of partnership assets into the one company, the outcome was virtually guaranteed over time. The same types of things can be said in distressed credit. The strategy is inherently risky and illiquid, but the fact that you have enhanced legal protections and influence over the direction of the company means you leave less up to chance. For a high-survival portfolio you want to be able to harvest the gains from one or two of these things but definitely not all three: Concentration, leverage, illiquidity. All of these things individually boost portfolio returns while lowering survivability. But a concentrated, levered, liquid portfolio can be liquidated, and an illiquid concentrated portfolio will not have to worry about leverage sinking it, a leveraged liquid portfolio which is diversified should still be able to trim and add where necessary. The other factor is beta… Some people try to buy high beta stocks because those stocks should theoretically provide higher returns through higher risk. I think this approach is suspect at best. I will cover this later but it appears to me that trying to buy companies that are high beta and hoping to harvest the returns that come with increased risk is a lesson in academia not always meeting reality. It is a well documented phenomenon that high beta stocks do much wore than theory would suggest and low beta does much better. These are exceptions, but being an active investor is the business of exceptions and rules of thumb. Because of that you have to know how to manage a portfolio of bets which you believe are exceptions, that i far different from just creating an index. here are some rules of thumb for sizing and diversification.

First, to continue with the activism analogy there are a few “thresholds”. With limited exception if you want management to meet with you then owning at least 0.1% of the company is a good starting place. Activists tend to buy 0.5-1%. My recommendation would be to only invest in companies where you can buy less than 4% of shares outstanding with 10% or less of total capital. Not a huge problem but for a firm with a billion dollars they cannot buy a company below 250 million on sheer principle. Anything after 4% will objectively take awhile to sell off. And the position would only be 1% of the portfolio

Personally I think you shouldn’t own more than 1% of shares outstanding if it will be less than 4% of assets. I have seen some huge activists who don’t follow this rule, but at this point in time it seems like you are sacrificing liquidity and likely do not want control.

10-30 total positions is a good starting point when all of the bets are non-path dependent. Fewer than ten total positions is rarely advisable under any circumstances without a large buffer in something like protective options, cash, or another safety diversifier.

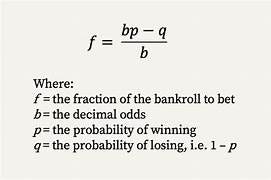

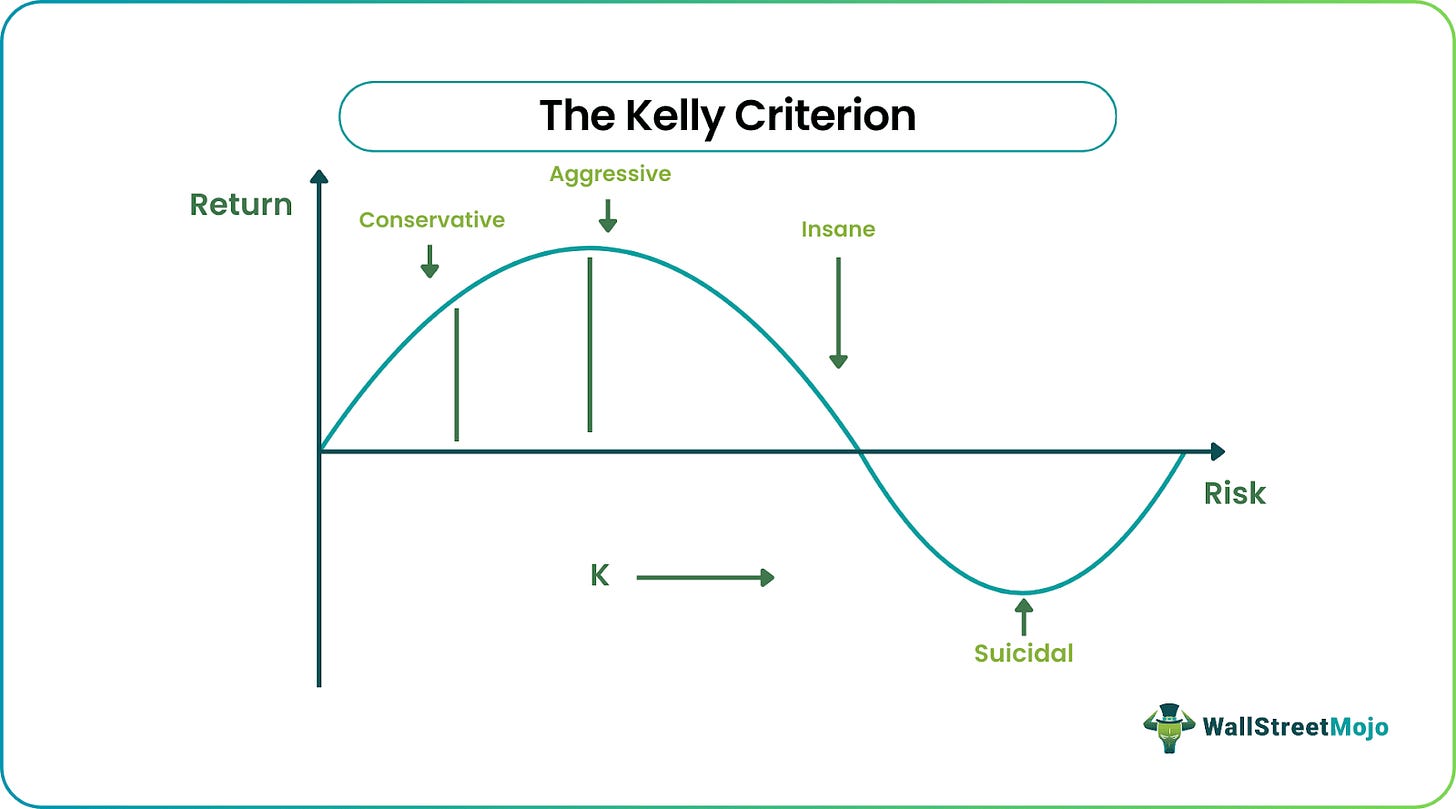

For sizing I like to use variations of the Kelly Criterion with sizing caps. First this requires an edge, essentially how certain are you in your analysis. You then find the probability weighted return of the investment.

You can also modify the Kelly formula for half-kelly or quarter-kelly. Essentially if the formula says to put down 20% you would put down 10% and so forth. The Kelly Formula is a tart, albeit an oversimplistic one. Assumptions for returns and percentage certainty should be updated consistently and there should be deference to avoiding large potential losses.

The more optimized way is conviction sizing, again as described by Alpha Theory. But here is the way I think about it. At cost I will never put more than 10% of my portfolio in any one stock. The general buckets for me are 1-2% 2-4% 4-6% 6-8% and 8-10%

I will also start trimming any company that exceeds 20% of the portfolio or I will sell or double any stock that falls below 0.5% these are general rules I set as guardrails. A standard position size will be 4-8%

10% will generally be for exceptional opportunities (META at 9x cashflow) or when we go activist. These are all rules of thumb but investors should be aware of these rules because it helps to create systems and helps you go from an artisan to a real manager. The other thing fundamental investors often lack is an understanding of market dynamics, in particular, factors.

Factor Awareness: Factors are the big thing in institutional money management. Factor-Neutral is the most common way allocators describe multi-manager hedge funds, which haven taken market share over the past decade. The idea is that there are risk factors beyond beta which contribute to returns. There is some debate over the idea of if factors and characteristics should be considered the same or not but the idea is this. Beyond basic beta stock prices move with a kind of “factor beta” be that a connection to something like profitability, price to book, market cap classification, or something like industry, or country. The idea is that certain stocks move in line with a “factor” designed to provide excess returns above beta, but this portfolio is essentially just taking on extra un-priced risks. Characteristics meanwhile are a statement about company fundamentals, not quant math. A stock could theoretically move perfectly in line with the value factor but be considered expensive. I bring this up because the data suggests that you want your portfolio driven by characteristics, not factors. The factors are not controllable at all, and just like the equity risk premium, different factors go in and out of favor all the time. But investors should monitor their factor exposure. Not to inherently try to be factor neutral or anything. But as an honest look at if your returns are driven by risk or luck, or if you manage to outperform idiosyncratically.

True net thinking. My final big thought this year came from a realization about turnover. I had a few positions where I entered and exited more like a trader than a long term investor. And I don’t mean with surgical precision, I mean I would hold for a few months then sell when nothing happened or I got spooked by a drawdown. The reality is that all of that activity creates increased tax costs for investors. The top tax rate on capital gains is 20%(with a few surcharges) but the top income tax rate which applies to short term capital gains, is 37%. That means for every 10% gain the short term gain will lose 1.7% more than the long term. It is also a lesson in patience. The best example for this was Nabors industries. An onshore oil driller in the United States with interesting projects around the world. At 43 dollars per share they were trading at less than 2026 Operating Cashflow but they proceeded to go below 30 dollars per share. They had a great Q3 but there was actually a negative response, which should have been a buy signal to me, but I simply held and now the stock is trading in the low 50s where I still believe they are undervalued. This thinking also applies to something like Hagerty, which I bought when they traded at a ridiculous multiple for any normal insurance company, the difference was I was confident in their ability to grow their earnings at an even more insane rate, and so far the market is rewarding that patience. While that same statement is not true for Kelly Partners I continue to hold the stock because I believe in the long term compounding power of the business as a safety net.

Overall my investing journey this year has given me an appreciation for stability, flexibility, and minimizing disaster not through paranoia but by minimizing the number of things that must go right.